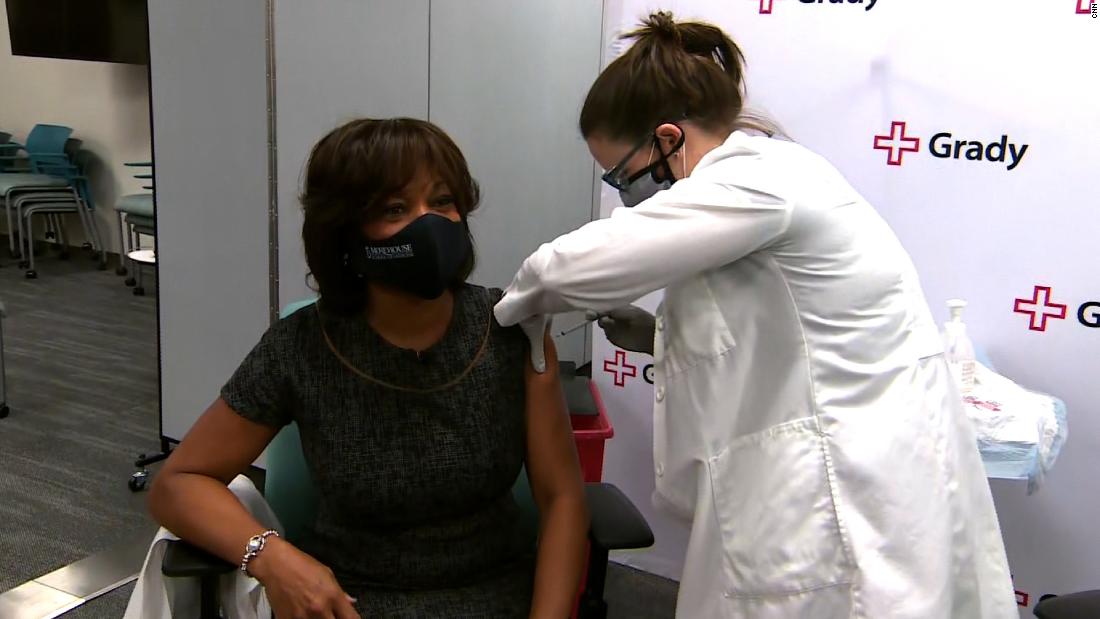

The Dean of Morehouse School of Medicine took her first vaccine against Covid-19 on CNN Friday morning with Dr. Sanjay Gupta at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. They’ll take the second shot in about three weeks.

Rice said she wouldn’t recommend anything she didn’t trust, and while she understands some Americans’ concerns about the history of racism in the country in medical research, she wants to assure people that the reality is different now.

“There are black scientists in the room where decisions are made. There are black scientists who are developing the vaccine,” Rice told Gupta.

There are also black scientists who sit on the FDA advisory panel and the CDC advisory board. And she added that there are people like her looking at the data.

The Morehouse School of Medicine is also working to disseminate information about the vaccine through fliers, webinars, panels, hotlines and is urging Black, Latino and Native Americans to participate in vaccine studies. People of color have been disproportionately affected by Covid-19 this year.

Morehouse is one of the historically black colleges and universities, black sororities and fraternities, and prominent black pastors leading national efforts to dispel the stigma surrounding the Covid-19 vaccine as much of black Americans are reluctant to include to make.

“We want to be that source of information that people can rely on and know that we will do our very best to get out of this pandemic for all of us,” said Immergluck.

Earlier this week, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams told CNN’s Jake Tapper that he met with the presidents of the Divine Nine – a group of nine black sororities and fraternities – to discuss efforts to create vaccine trust in the black community. .

“We represent every culture of black people in the United States,” said Peters. “We have a legacy of trusted individuals in the community who go out selflessly to serve humanity.”

Peters said the task force is focused on reviewing data for all vaccines before bringing the information to the community. Peters said he wants to make sure the fraternity promotes a vaccine that is safe – especially for pregnant women and people with pre-existing conditions – and highly effective.

Once the task force is confident in the data, it will start working with churches, local fraternity departments, barber shops and use social media to encourage people to take the vaccine, Peters said.

“We want the vaccine with the strongest efficacy,” said Peters.

“I trust my profession is deeply rooted in science,” says the nurse

According to a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 35% of black Americans say they would probably or certainly not get the vaccine if it was determined by scientists to be safe and freely available everywhere.

The study found that black people who don’t trust the vaccine are largely concerned about possible side effects – which doctors say are mild – and think they could get Covid-19 by taking the vaccine.

The Tuskegee experiments of 1932-1972 recruited 600 black men – 399 who had syphilis and 201 who did not – and followed the progress of the disease by not treating the men when they died or suffered serious health problems.

When Pfizer launched the first shipments of its vaccine this week, some black nurses and doctors videotaped the vaccine live this week to combat fears in the black community.

Among them was Sandra Lindsay, an intensive care nurse at Long Island Jewish Medical Centers, who received the injection Monday from Dr. Michelle Chester, the corporate director of employee health services at Northwell Health, who is also black.

“I have no fear. I trust my profession is deeply rooted in science …” Lindsay told CNN’s Anderson Cooper. “What I don’t trust is getting Covid-19 because I don’t know how it will affect me and those around me to whom I could potentially transmit the virus.”

On Wednesday, some 50 black ministers of the Choose Healthy Life Black Clergy Action Plan held a Zoom Summit with Dr. Anthony Fauci, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, and Dr. Tom Frieden to discuss health inequalities in the black community and Covid-19 to fight. and the introduction of the Covid-19 vaccine.

Choose Healthy Life is a partnership of black churches across the country that aims to combat the impact of the pandemic on the black community. The group has moved from offering free Covid-19 tests earlier this year to launching a national awareness campaign to increase awareness of the vaccine.

Top reviews highlighted the importance of black clergy and the country’s top doctors working together to ensure a successful rollout of the vaccine, Choose Healthy Life said.

“As religious leaders, it is our duty to advocate for the health and survival of our community, provide our congregations with accurate information, and guide society as a whole to a place of moral well-being,” said Rev. Al Sharpton , Co-chair of the Action Plan Choose Healthy Living Black Clergy. “As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, religious leaders should serve as a thermostat that transforms society, not a thermometer that measures temperature and allows social pressures to influence it.”

“Skepticism is real,” but groups dispel misinformation

Barbershops and hair salons have also become central to the conversation about vaccines as they are cornerstones in the black community.

Stephen Thomas, professor of health policy and management at the University of Maryland at College Park, hosts Zoom town halls where doctors and scientists teach hairdressers, stylists, and their Maryland clients about the vaccine.

The effort is part of Thomas’ Health Advocates In-Reach and Research, or HAIR, initiative that provides cancer screenings at barber shops and hair salons.

Thomas said the town halls are helping to dispel misinformation surrounding the vaccine.

“The hairdressers and the stylists are confident,” said Thomas. “It’s a big deal, it’s a family affair. It’s a place where black people come together across all their socio-economic divisions.”

Elsewhere, civil rights leaders, including Sharpton, activists and doctors in New York, formed a task force to address black community concerns about the vaccine and create fair access. Leaders say they hope the task force can become a national model for black communities.

The task force plans to run an aggressive campaign that it says will distribute accurate information about the vaccine.

Jennifer Jones Austin, a task force member and executive director of the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies, said many black and brown people have been marked by differences in healthcare for decades and will not take the vaccine without their questions answered by trusted leaders.

“The skepticism is real,” said Austin. “We need to do the work to help people understand why this vaccine can be of value and a great resource for controlling the disease.”