LAMESA, Texas – Running between patients, Dr. Eileen Sprys pauses to catch her breath, tries to gather, but can’t hide her frustration: West Texas-besieged COVID hospital workers were left out of the first transport the vaccine Pfizer and BioNTech and have no idea when they can get it.

No rural hospital in this state that is proud of its roots in the country has received any vaccine doses this week, despite these medical outposts serving about 20% of the state’s population, or 3 million people.

Even before the pandemic, rural hospitals in Texas and many other states operated with “skin and bone” staff and budgets, Sprys said.

“We are all exposed all the time,” she said. “We don’t have an isolated COVID wing or dedicated COVID staff, unlike larger hospitals. Not being included in the first vaccine shipment is so annoying.”

This is not the first sign of inequality in the pandemic. Poor people in rural and urban areas of the United States have complained that they do not receive treatment and medication all the better, nor the quantity or quality of tests.

Sprys, his three medical colleagues and 28 nursing staff at Lamesa Medical Arts Hospital have been waiting for the vaccine for months, hoping it will bring relief to Dawson County.

One of the poorest counties in Texas, nearly a quarter of Dawson’s 13,000 people live in poverty. To date, it has recorded 1,325 coronavirus cases and 42 deaths, according to the state health department.

Rural hospitals across the country, and especially in Texas, are facing widespread closures after years of budget cuts. About 27 rural hospitals have closed in Texas in the past decade – twice as many as any other state.

Had it not been for a $ 10 billion federal incentive for rural hospitals nationwide in May, half a dozen other small Texas facilities would have closed, estimates John Henderson, president of the Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals in Texas. Texas.

Needles in your arms

The Texas State Department of Health is tasked with allocating the vaccine. An expert group of 17 people is in charge of sending recommendations on the distribution of the state health commissioner, Dr. John Hellerstedt, who has the last word on deliveries.

In a December 14 letter to rural health advocates, Hellerstedt praised their patience and wrote that a “more inclusive” vaccine strategy would begin next week and that the pending approval of the Moderna vaccine would help alleviate deficiencies in rural health. rural environment.

Chris Van Deusen, a spokesman for the state health services, said there were two major reasons why rural areas were left out of initial Pfizer vaccine deliveries. The first is that the smallest shipment contains 975 doses, so the state sent it to hospitals, which said they needed many inoculated health workers.

The second reason is that the Pfizer vaccine should be stored in special freezers, which larger facilities were more likely to have. But this reasoning annoys the doctors in Lamesa because their hospital had bought one of these freezers in advance.

The Moderna vaccine, Van Deusen said, is easier to store and can be delivered in at least 100 doses, which means it can go to smaller hospitals.

Time is of the essence, said Henderson of the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals.

“You only have one doctor because of the coronavirus in a small town, and that could mean you’ve just lost half your medical staff,” he said.

Henderson said the state should embrace alternatives – such as the fact that regional medical centers should not vaccinate lower-risk staff and instead allocate doses to front-line rural doctors and nurses.

“Answer the call”

It is difficult to recruit doctors to work in any small town, and those who do are considered the crown jewels of their communities. Many residents interviewed in Lamesa said they were convinced that their medical staff should be protected immediately.

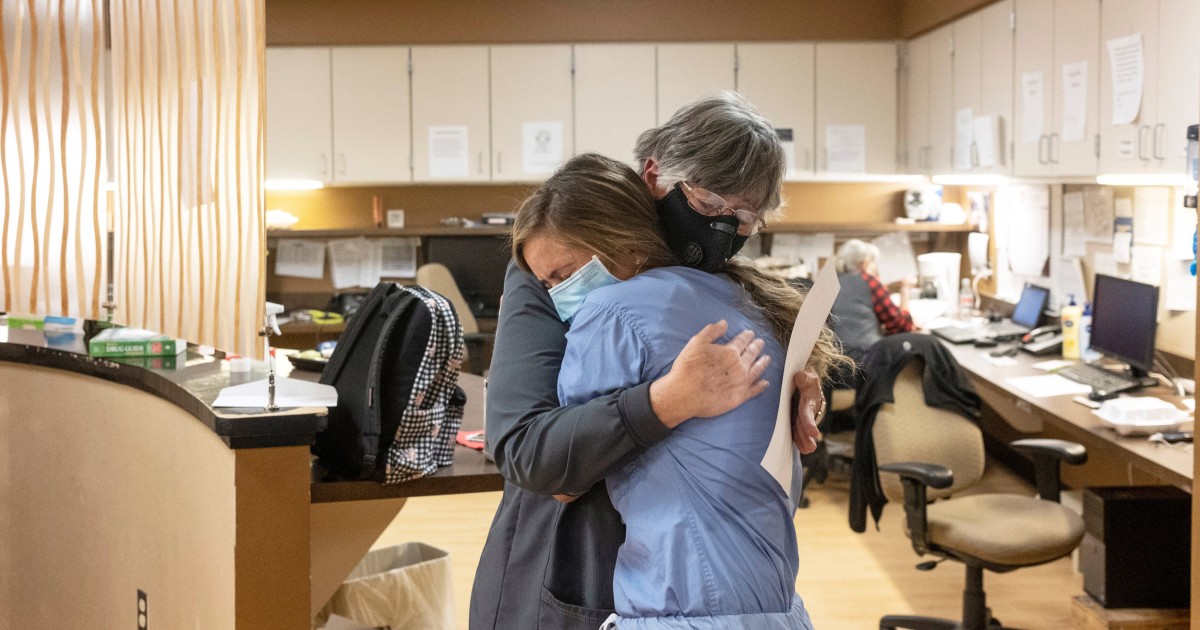

Debbie Aylesworth, 67, admits to Sprys and staff at Lamesa Hospital that she kept her from the ventilator when she had COVID-19 a few months ago. After Aylesworth was exposed to the virus in October, Sprys sent her a daily message asking if she had any symptoms.

If not for Sprys’ insistence, Aylesworth said he would probably be late for treatment and it would be much worse.

“Those doctors answer the call,” she said. “They are dealing with the worst of this pandemic, so they should see the benefits of the vaccine.”

Josh Stevens, the mayor of Lamesa, said the area was as brutalized by the pandemic as anywhere in Texas.

To make matters worse, he said, is that about 85 percent of the city’s population is considered part of the essential workforce – most of whom work in agriculture along with oil and gas – meaning more citizens in Lamesa have come out on top. line.

“Most people in Lamesa had nowhere to hide from this virus, and our doctors had to deal with this reality,” he said. “Not being on the front line to get a vaccine is a slap in the face for all of rural Texas.”