The coronavirus pandemic has had the world fixed on viruses like no moment in living memory, but new evidence shows that humans do not even notice the vast expanse of viral existence – even when they are in us.

A new database project compiled by scientists has identified more than 140,000 viral species living in the human gut – a huge catalog that is all the more astonishing as more than half of these viruses were previously unknown to science.

If tens of thousands of newly discovered viruses sound like an alarming development, it is completely understandable. But we should not misinterpret what these viruses actually mean to us, say the researchers.

“It is important to remember that not all viruses are harmful, but they are an integral part of the intestinal ecosystem,” said biochemist Alexandre Almeida of the Institute of Bioinformatics at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

These samples came mainly from healthy individuals who did not have specific diseases.

The new catalog of viruses – called the intestinal phage database (GPD) – was respected by analyzing more than 28,000 individual metagenomes – records available to the public for DNA sequencing of samples of intestinal microbiomes collected from 28 countries – along with almost 2900 of reference genomes of cultured intestinal bacteria.

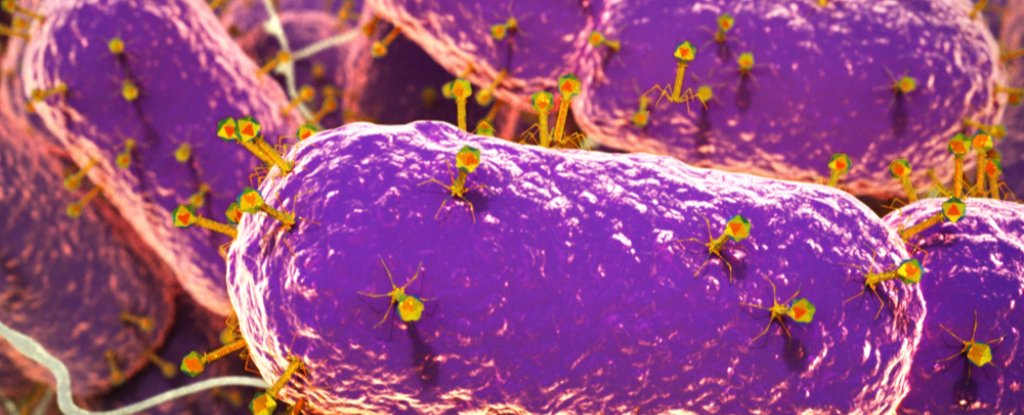

The results revealed 142,809 viral species living in the human gut, a specific type of virus known as a bacteriophage, which infects bacteria in addition to single-celled organisms called archaea.

In the mysterious environment of the intestinal microbiome – inhabited by a diverse mixture of microscopic organisms, which includes both bacteria and viruses – it is believed that bacteriophages play an important role, regulating both bacteria and human gut health.

“Bacteriophages … profoundly influence microbial communities by functioning as horizontal gene transfer vectors, encoding ancillary functions beneficial to host bacterial species and promoting dynamic co-evolutionary interactions,” the researchers write in their new paper.

For a long time, our knowledge of this phenomenon was blocked by the limitations of understanding bacteriophage species.

In recent years, new advances in metagenomic analysis have significantly expanded our awareness of the viral variety we are looking at here – and perhaps nothing more than the intestinal phage database, which researchers describe as an “expansion of the bacteriophage diversity of the human gut. “

“To our knowledge, this set is the most comprehensive and complete collection of human intestinal phage genomes to date,” write the study’s authors.

Having a comprehensive database of high quality phage genomes paves the way for a multitude of analyzes of the human gut virus at a much improved resolution, allowing the association of specific viral clades with distinct microbiome phenotypes.

Already, the database updates what we know about viral behavior.

Research shows that over a third (36 percent) of identified viral groups are not limited to infecting a single species of bacteria, which means they can create gene flow networks between phylogenetically distinct bacterial species.

In addition, researchers found 280 viral clusters distributed globally, including a newly identified clade called Gubaphage, which appears to be the second most widespread clade of virus in the human gut, after what is known as the crAssphage group .

Given some similarities between the two, the researchers initially thought that Gubaphage may have belonged to a family of crawling-like viruses before determining which clades were, in fact, distinct.

There is so much more to learn and not just on Gubaphage – but on more viruses than we have ever dared to dream of. Thanks to such research efforts, however, tomorrow’s discoveries are closer, and new perspectives will come sooner.

“Bacteriophage research is currently experiencing a renaissance,” said microbiologist Trevor Lawley of the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

“This high-quality, large-scale catalog of human gut viruses comes at the right time to serve as a model to guide ecological and evolutionary analysis in future studies of the virus.”

The findings are reported in Cell.