Twenty million years ago, the shores of northern Taiwan were sandstone sediments at the bottom of the sea, where 6-meter-long worms lurked in burrows, waiting for unsuspected prey to surface.d. Now, a team of geologists has analyzed 319 fossils of traces of those marine carnivorous worms, whose pits fossilized in Miocene snow.

“At first, we were firmly convinced that it was a very elegant shrimp den,” Ludvig Löwemark, a sedimentologist at Taiwan National University, said in a video call. “And then, after talking to other experts, we leaned towards this bivalve hypothesis. But eventually, I became more and more convinced that it was actually a bobbit worm that did this. ”

Traces of fossils are vestiges of the creatures that made them – footprints and other hardened remains of the movements of living animals, rather than the fossil remains of the creatures themselves. Researcher worms suggest that once inhabited, these burrows have long since disappeared, probably composed of soft tissues that deteriorated shortly after death. An analysis of the fossils is published today in the journal Scientific Reports.

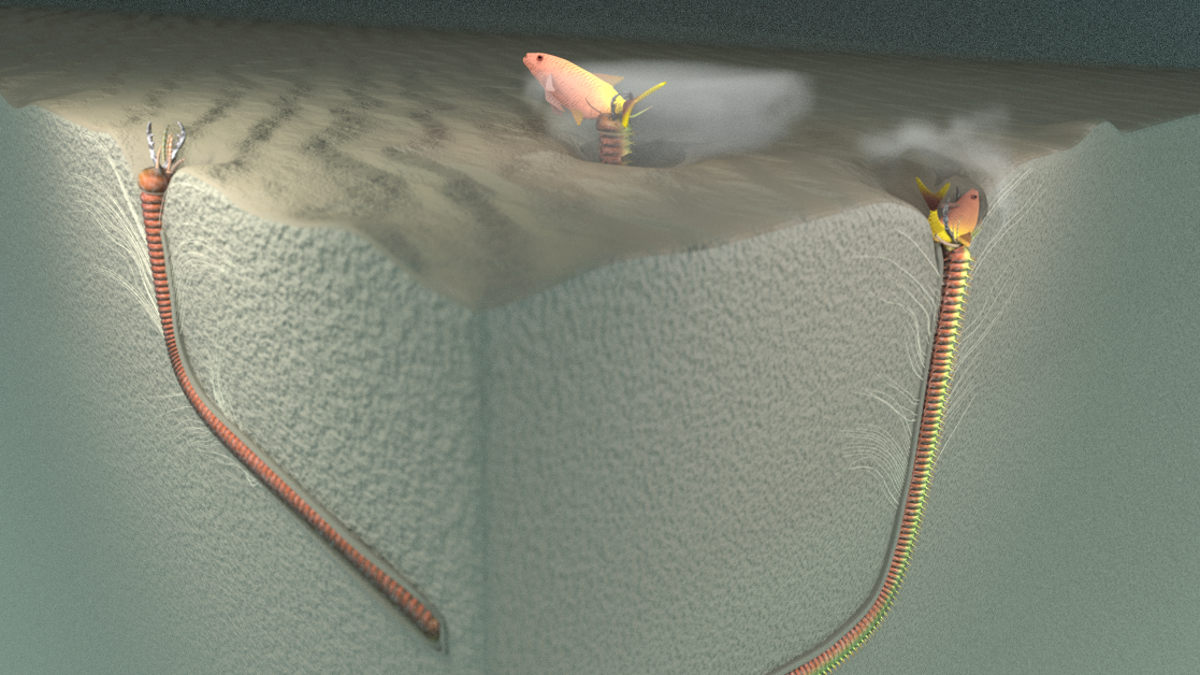

Löwemark’s team, led by Yu-Yen Pan at Taiwan’s National University, discovered hundreds of hotspots that throw Taiwan’s rocky shore. They found the holes turned horizontally as they went deeper, forming a boomerang-shaped burrow about 1 inch wide and 6 feet deep. The conical bending of the den suggested to the team that the ground beneath the creature either became harder to dig at a certain depth or became more anoxic. (Worms breathe through the skin, so if the soil in which they are submerged does not have enough oxygen, it can be fatal).

G / O Media may receive a commission

Where the burrows opened on the bottom at the time, there was a “feathered” pattern that the team identified, suggesting that the bottom of the silken sea had collapsed around the structure in a funnel shape, indicative of a vacuum left by a creature. throwing herself back into her lair. They concluded that the animals that made burrows are close relatives of the killer bobbit worms, which still grow up to 10 meters long and have been named for an infamous Criminal case in the 1990s involving a severed penis (although it might be time to Change that name). They are called fossil traces from Taiwan Pennichnus beautiful!, which means “beautiful feather traces”, the last name derived from the Portuguese name for Taiwan, Formosa.

“It doesn’t matter who did it – it’s the shape and function of the fossil record that gets its name,” Löwemark said. “So you have a genus for similar traits, fossils that were produced in a specific way, because of their feeding behavior or locomotion or whatever … and then you have a species name.”

After eliminating other culprits – the shrimp would have left the “twisting” chambers in the pits, while the worms would be more of a one-way operation, and a bivalve suspect would have had a cul-de-sac marking the den where he was doing. place for the shell – a predatory ambush worm seemed to fit the profile. Today, the bobbit worm hunts by feeling: When it feels a disturbance outside its lair, the worm throws itself at the still unidentified body of lightning, armed with hardened tongs. When it has a good restraint, the worm takes out its prey in the den and the sand collapses over the entrance, hiding the scary scene. If you blinked, you would never know it happened.

“It’s a very brutal procedure,” Löwemark explained.

When you think about it on a large scale – the team found hundreds of these burrows in two places along the coast – it sounds like a terrifying game and vice versa of whack-a-mole.