Because Philadelphia is facing a deadly pandemic and its effects on the existing opioid crisis, research suggests that black residents have been particularly affected by fatal overdoses since the onset of COVID-19.

Fatal overdoses among black residents increased by more than 50% in the months following the Pennsylvania home stay order, compared to the same time period the previous year. Overdose deaths among white residents declined significantly during this period.

Researchers at Penn Medicine looked at trends in opioid overdose published last year by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and the Philadelphia Fire Department after seeing signs of an increase in the number of deaths among black residents. Their findings mark a reversal of trends generally observed in the opioid epidemic.

“Philadelphia was devastated by the opioid crisis, which was previously more acute in the white community,” said Dr. Utsha Khatri, emergency physician and lead author of the study, published in the JAMA Network Open. However, recently, we have seen a disturbing trend toward higher rates of fatal and non-fatal overdoses among Black Philadelphia residents. These differential trends in opioid overdose suggest that racial inequalities have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

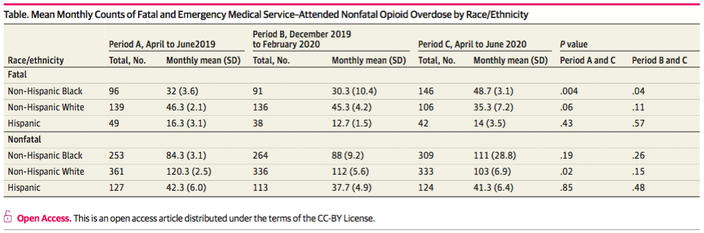

The study examined three separate time periods:

• Period A – April to June 2019

• Period B – December 2019 until February 2020

• Period C – April to June 2020

The researchers chose period C to coincide with the entire months following the home stay order, while period A provided a year-on-year comparison, and period B showed the months leading up to the pandemic.

Overall, fatal overdoses remained relatively unchanged in Philadelphia in a year-over-year comparison between period A and period C. The city had an average of 94 overdose deaths per month in period A and 98 deaths per month in period A. C.

But among black individuals, overdose deaths increased from a monthly average of about 30 in periods A and B to about 49 in period C.

Fatal overdoses among white residents of Philadelphia fell from a monthly average of 46 and 45 in periods A and B, and only 35 in period C. This marked a 31% year-over-year decrease and a decrease. of 22% compared to the previous period. pandemic time interval.

Among Hispanic residents, the average number of monthly deaths decreased from about 16 to 12 in period A in period B, but then increased to about 14 in period C.

Similar racial trends were detected in non-fatal Philadelphia overdoses.

JAMA open source / network

JAMA open source / network

Penn researchers have published their demographic findings on opiate deaths in Philadelphia in the JAMA Network Open.

“The results of this study are worrying, “said senior author Eugenia South, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Penn.” The black community has been severely affected since the beginning of the pandemic – both by the disease itself and by social and economic issues. consequences, which include increased gun violence, job losses and the closure of small businesses. We believe that the increase in fatal and non-fatal opioid overdoses is a symptom of this. “

The release of the study comes as the city’s health department faces changing causes and demographic data on the opioid epidemic.

Preliminary statistics for 2020 include a total of 950 deaths from January to September. When all the information is recorded and verified, 2020 is expected to be the deadliest year in the city for opioid overdoses.

Much of this has been attributed to the continued rise in deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl, which is increasingly occurring in drug mixtures with methamphetamine, PCP and cocaine, in addition to heroin. The health department warned this week that “fentanyl is in everything,” providing statistics on fentanyl-related overdose deaths combined with other drugs in recent years.

The Penn research team believes that the increasing prevalence of fentanyl may partly explain why fatal overdoses have increased among blacks.

“How this translates into an increase in accidental drug overdoses is unknown, but may be related in part to the purchase of cheaper drugs from less familiar sources,” said study co-author Kendra Viner, the leader. division of the health department for substance use prevention. “Our concern is that fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that is cheaper to produce and distribute, is increasingly found in non-opioid drugs. This can put populations of drug users without prior exposure to opioids at a higher risk of overdose. “

The researchers also theorized that access to opioid treatment remains unfair. Buprenorphine, a prescription drug used to relieve opioid cravings, remains more available to white patients than black patients.

And while research shows that drug use tends to be quite similar between races, people of color are more likely to face legal sanctions for it. The treatment has not been effective enough to reach people who are already involved in the criminal justice system.

The study was limited to Philadelphia, but researchers believe similar trends in opioid overdose deaths in other US cities may become apparent through closer analysis. The study’s authors say health departments publicly report racial opioid overdoses.

“Cities across the country need to look at overdose trends in different socio-demographic groups in order to have a more detailed understanding of those affected and how best to target response efforts,” Khatri said.

The Department of Health is currently developing a community education initiative to raise awareness and prevent overdoses involving mixtures of fentanyl drugs. The program will include the distribution of test strips of fentanyl and naloxone, the anti-overdose drug used to counteract the effect of opioids.

The city will also expand public training on the recognition of opioid overdose and naloxone use, advocate for wider access to buprenorphine, and provide more support for so-called “hot transfers” to health care drug treatment, prison and community settings.

The Penn study was supported by grants from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.