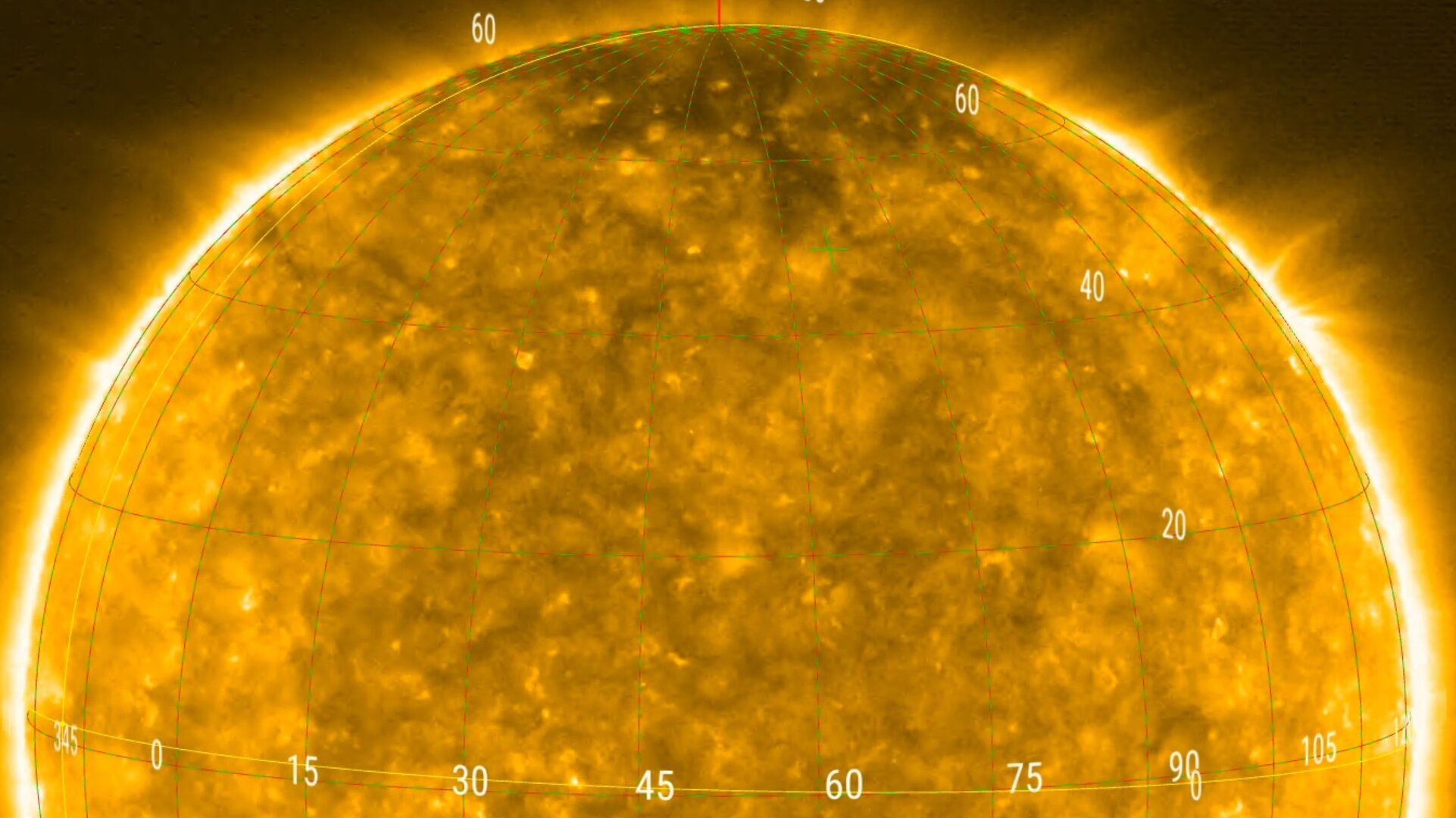

One of the best things about astronomy is that it is an endless source of wonderful images. Almost every new mission or telescope offers new ways to see the universe and, when translated visually, can provide absolutely stunning images of some of the most interesting places in that universe. Humanity is now beginning to process images from one of the newest sky-raising missions: the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter. And the boy are those amazing images.

The data that scientists analyze is collected using ten different instruments composed of both telescopes and in situ instruments. They collaborated to provide data sets (and, in some cases, images) with three very different phenomena.

The first set of data focuses on the most unpredictable environmental conditions – the weather. In this case, however, space weather and, specifically, solar winds are occasionally emitted by the sun itself. Solar Orbiter’s in situ instruments were able to calculate where the solar wind blowing the spacecraft came from. A special wind they were monitoring in June 2020 seemed to come from near a “coronary hole”, where the sun’s magnetosphere allows the wind, which is normally contained by the sun, to be expelled into space.

Credit: ESA

Another interesting set of space-time data was the role of the Solar Orbiter in a multi-point assessment of a coronal mass ejection (CME). CME was directed as a Solar Orbiter while aligned between the sun and Earth, so CME continued to pass over the orbiter and eventually hit Earth a few hours later. The Earth’s orbit at that time was BepiColombo, ESA’s first mission to Mercury. BepiColombo also picked up the signal for CME when it hit Earth.

There was a third satellite that also contributed additional data points – Stereo-A, a NASA mission that observed the sun since 2006. It initially took over the CME as it was emitted by the sun and was able to track how hit Solar Orbiter and BepiColombo in turn. The data points from all these three platforms can be used to help analyze any interesting aspects of this, and potential of other CMEs.

Credit: ESA

Strangely, there was another probe that barely noticed CME, even though it was designed specifically to detect phenomena like this. SOHO, an orbiter observing the 1995 sun, barely noticed when it was hit by CME while it was at Earth’s L1 LaGrange. Additional data from the observatory would have led to a further increase in the treasure already collected, but now scientists need to discover the absence of data, rather than their significance.

The second set of data refers to the “campfires” that were first observed in the first batch of Solar Orbiter images earlier this year. Research teams have begun to suggest that campfires may in fact be the much-sought-after “nano-flare” that has been theorized to cause the sun to heat up.

Credit: ESA

However, a definitive answer is not yet in the bag, as additional data will need to be collected, especially on the energy levels of the campfires. According to Frédéric Auchère, chairman of the Solar Orbiter remote sensing working group, “At the moment, we only have commissioning data … and the results are very preliminary. But clearly we see very interesting things. “

The third data set comes from a slightly serendipitous cosmic synchronization. When Solar Orbiter was launched, program managers noticed that it would pass through the tail of comet ATLAS. This provided a unique opportunity to collect some additional data, even though the Solar Orbiter instruments were not designed for a cometary encounter.

Credits: NASA, ESA, STSci and D. Jewitt (UCLA)

What made the meeting even more interesting is that ATLAS disintegrated in April 2020, before Solar Orbit reached the queue. Although there was a chance that the spacecraft would not detect anything at all due to the comet’s disintegration, it actually brought peaks in magnetic signatures, as well as high interstellar dust spots. As Tim Horbury, chair of the Solar Orbiter in-situ working group, points out, “This is the first time we’ve essentially traveled after a disintegrated comet.”

While there will probably be no images from Solar Orbiter about the comet’s disintegration, there have been some amazing ones from Hubble. And Solar Orbiter continues its mission of collecting data with a few Venus flybys and an exceptionally close approach to the sun, there are probably some stunning images of the nearest star to come.

Find out more:

ESA: Solar Orbiter: transforming images into physics

UT: I’m inside! The first images from ESA’s Solar Orbiter

Space.com: Solar Orbiter makes its first flight from the sun

Lead Image Credit: Image of the sun from Solar Orbiter. Credit: ESA