Monkey embryos containing human cells were produced in a laboratory, a study confirmed, stimulating a new debate in the ethics of such experiments.

Embryos are known as chimeras, organisms whose cells come from two or more “individuals” and, in this case, different species: a long-tailed macaque and a human.

In recent years, researchers have produced pig embryos and sheep embryos that contain human cells – the research they say is important, as one day it could allow them to grow human organs inside other animals, increasing the number of organs. available for transplant.

Now scientists have confirmed that they have produced macaque embryos that contain human cells, revealing that cells could survive and even multiply.

In addition, the researchers, led by Prof. Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte of the Salk Institute in the USA, said that the results offer a new perspective on the communication pathways between the cells of different species: works that could help them in their efforts to make chimeras with species that are less closely related to ours.

“These results may help to better understand early human development and the evolution of primates and to develop effective strategies to improve human chimerism in evolutionarily distant species,” the authors wrote.

The study confirms rumors reported in the Spanish newspaper El País in 2019 that a team of researchers led by Belmonte produced monkey-human chimeras. The word chimera comes from a beast in Greek mythology that was said to be part lion, part goat and part snake.

The study, published in the journal Cell, reveals how scientists took certain human fetal cells called fibroblasts and reprogrammed them to become stem cells. They were then introduced into 132 long-tailed macaque embryos six days after fertilization.

“Twenty-five human cells were injected and, on average, we observed about 4% of the human cells in the monkey’s epiblast,” said Dr. Jun Wu, co-author of the research now at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

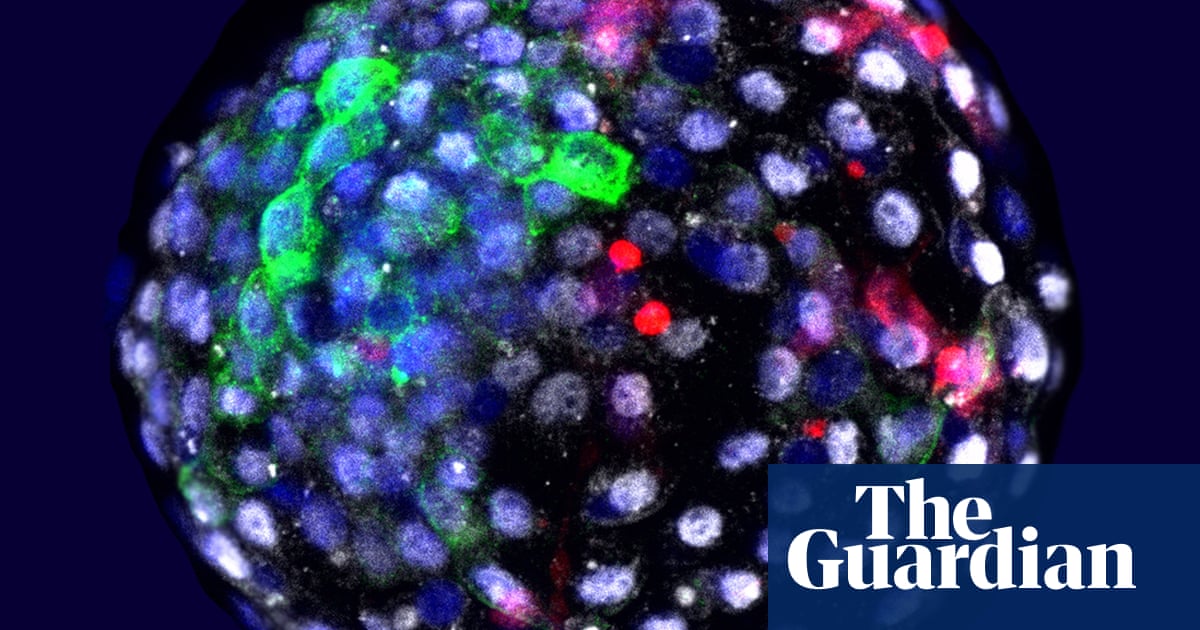

The embryos were allowed to grow in Petri dishes and were discontinued 19 days after the stem cells were injected. To verify that embryos contain human cells, the team designed human stem cells to produce a fluorescent protein.

Among other findings, the results show that all 132 embryos contained human cells on the seventh day after fertilization, although as they developed, the proportion containing human cells decreased over time.

“We have shown that human stem cells have survived and generated additional cells, as would normally happen as primate embryos grow and form the cell layers that eventually lead to all the organs of an animal,” he said. said Belmonte.

The team also reported that they found some differences in cell-cell interactions between human cells and monkey cells in chimeric embryos, compared to monkey embryos without human cells.

Wu said he hopes the research will help develop “transplantable human tissues and organs in pigs to help overcome the shortage of donor organs worldwide.”

Prof. Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London, said at the time of the El País report that he was not concerned about the ethics of the experiment, noting that the team only produced a ball of cells. However, he mentioned that puzzles could arise in the future if he allowed the embryos to develop further.

Although it is not the first attempt to make ape-man chimeras – another group reported such experiments last year – the new study has rekindled such concerns. Prof. Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford Uehiro Center for Practical Ethics and co-director of the Wellcome Center for Ethics and Humanities at Oxford University, said the research opened a Pandora’s box for human-inhuman chimeras.

“These embryos were destroyed within 20 days of development, but it’s only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans,” he said, adding that a question Key ethics goes beyond the morality of the status of such creatures.

“Before performing any experiments on live-born chimeras or their extracted organs, it is essential that their mental abilities and life be properly assessed. Which shows that a non-human animal can be mentally close to a human being, “he said.” We will need new ways to understand animals, their mental life and relationships before they can be used for human benefit. “

Others expressed concern about the quality of the study. Dr Alfonso Martinez Arias, an associate professor in the Department of Genetics at Cambridge University, said: “I don’t think the findings are supported by solid data. The results, insofar as they can be interpreted, show that these chimeras do not work and that all experimental animals are very sick.

“Importantly, there are many human embryonic stem cell-based systems to study human development that are ethically acceptable, and ultimately we will use this rather than chimeras like the one suggested here.”