Viruses move; it does the same thing, really. But experts are now worried about some of the thousands of coronavirus variants that have appeared around the world. I wrote about the UK version last month; now there are several, including one in Los Angeles. You don’t have to panic. But it’s good to be informed.

One of the major reasons we see new variants now, a year after the pandemic, is that there is much more virus than there was 12 months ago. The more viruses there are in the world, the more likely they are to move. And the more options there are, the better the chances that some of them will be bad news.

If we (as a global community) had done a better job of containing the virus in the first place, we might not have gotten to the point where there are several variants that are different enough to worry the experts. But here we are.

Another thing to remember is that you will only find variants if you look for them. The British variant, B.1.1.7, was partially discovered because the UK does a lot of so-called surveillance tests – monitoring exactly what types of coronaviruses are there. The US is also part of that, but much less so. Variant B.1.1.7 was probably already in other countries until it was discovered in the UK; they had simply not found her yet.

G / O Media may receive a commission

What are the options to know?

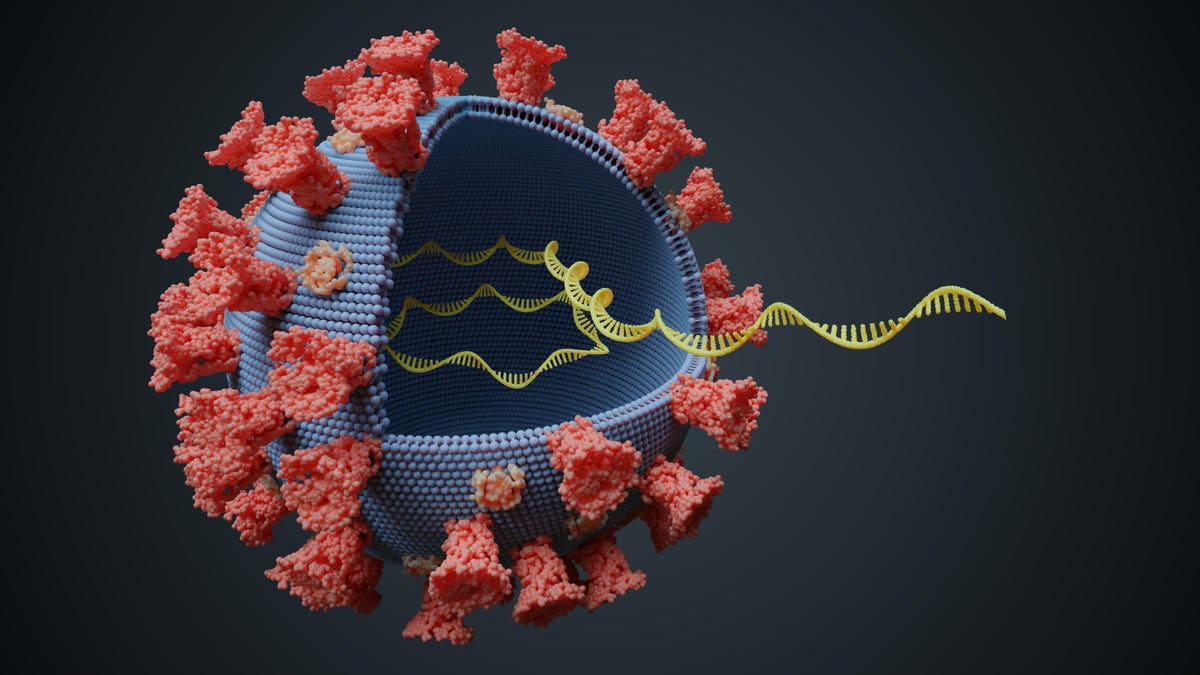

B.1.1.7 was found in November 2020 in the UK, where it has been circulating probably since September or earlier. This article from the New York Times has more details about the strain and its mutations. It appears to be 50% more transmissible than a typical COVID virus. It has multiple mutations, including eight on the protein spike.

(Spike protein is the part of the virus that interacts with our cells. When we produce antibodies against spike protein, these antibodies can stop the virus from infecting us. MRNA vaccines include the genetic code of spike protein, which allows our cells to produce protein and then produce antibodies against it.)

B.1.1.7 is more communicable, but the disease it causes does not appear to be worse than usual.

B.1.351 was discovered in South Africa in samples dating back to October 2020 and also has mutations in the spike protein. It appears to be more transmissible than typical COVID, but does not alter the severity of the disease. Both this variant and the one in Great Britain share a mutation called N501Y. A recent study, posted as a prepress, found that the Pfizer vaccine do what they seem to protect against variants with this mutation.

P.1 is a variant from Brazil, first detected in December 2020. It also has mutations that seem worrying, including for the spike protein. One of its mutations, E484K, may be able to evade antibodies; there are some reason to suspect that people who have recovered from a previous case of COVID may be infected by these mutations.

CAL.20C is a variant that is becoming popular in Los Angeles. We don’t know much about that yet.

For all these variants, science is still very new. The things we know about them are temporary. None of them seem to cause more severe diseases; most are likely susceptible to existing vaccines; and PCR tests still seem to be able to detect them.

They have also often become the dominant strains in their locations, but for some variants there is a problem with eggs and chicks in determining whether they are responsive for peaks in cases or not.

What happens now?

Two things. First, scientists are working on answering unanswered questions about these options.

For example, we need to find out if they are really more transmissible and, if so, by how much. We need to know if the variants can steal our natural immunity (which would mean you could catch the virus twice) and if they can steal immunity from the various vaccines and vaccine candidates that already exist. We need to know if any of the variants cause more severe diseases or if there are clinical differences. And we need to expand our surveillance, in each country, to be able to find new variants as they appear and to follow where they take over the existing variants.

Over time, if it turns out that new variants can steal existing vaccines, it may be necessary to update the vaccines. We do this for the flu vaccine every year; we may have to do the same for the COVID vaccine.

But the other element of action is simpler, even if it is difficult: we have to do the same things we did for prevention, only to a greater degree. If a variant is more transmissible, it is even more important to wear masks and stay at home and take the tests seriously. It is additional, additional important to bring vaccines to people as soon as possible. So in this sense, even if the virus changes, the most important measures to control it have not changed.