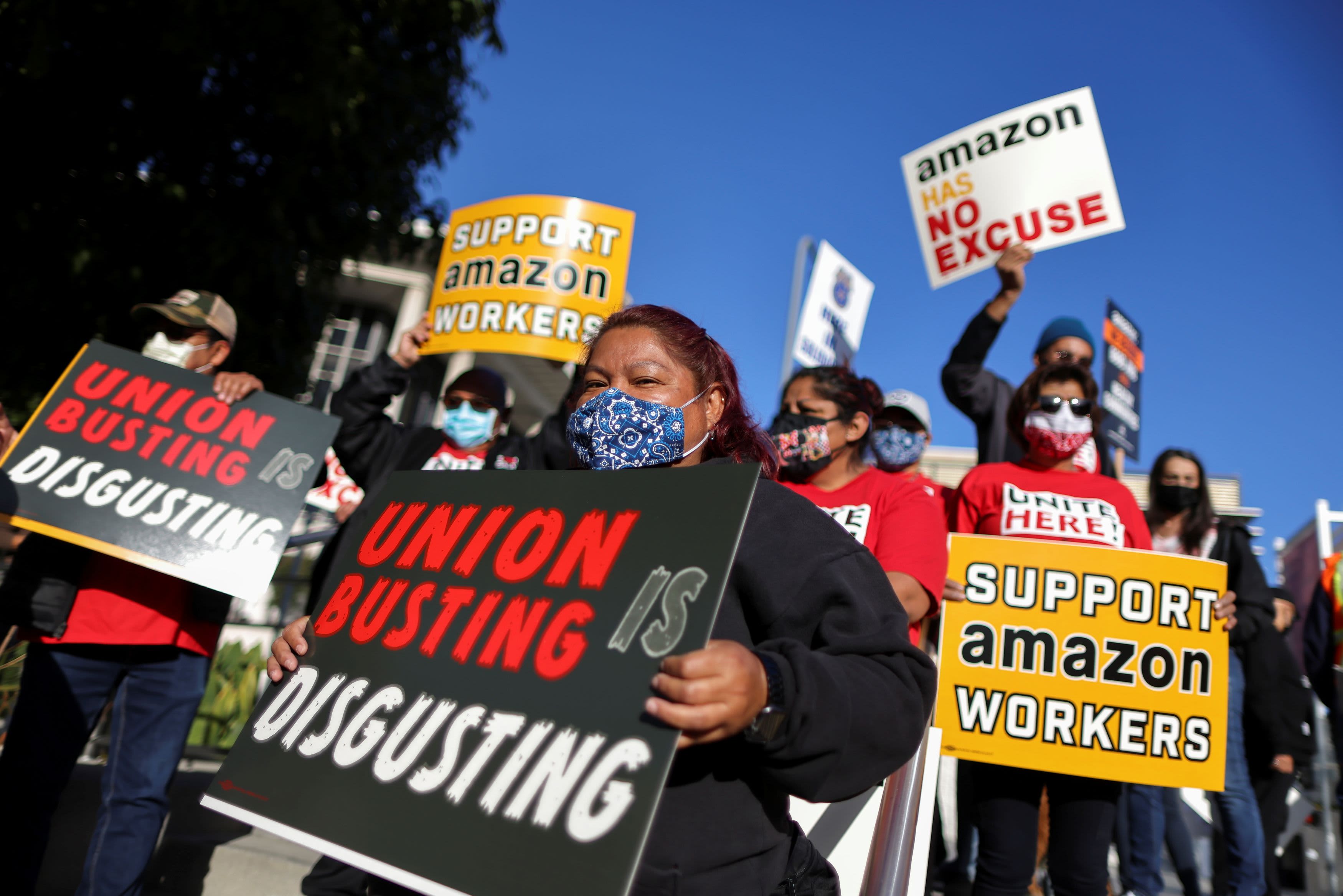

People are protesting in support of the unionization efforts of Alabama Amazon workers in Los Angeles, California, March 22, 2021.

Lucy Nicholson | Reuters

Last week, Amazon strongly defeated union unity at one of its warehouses in Alabama, a major victory for the e-commerce giant, which has long fought attempts to unionize its facilities.

Workers at the Bessemer, Alabama depot voted overwhelmingly in favor of rejecting unionization, with less than 30 percent of the vote in favor. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store union, which led the union, intends to challenge the result, arguing that Amazon violated the law with some of its anti-union activity before and during the vote.

The result is an obstacle to organized work, which he hopes the Bessemer election will help establish a foothold at Amazon. But unions, workers’ lawyers and some employees at the Bessemer unit, known as BHM1, said they believe the Bessemer election will continue to fuel attempts to hold other warehouses across the country. Labor leaders say the Bessemer election also revealed to the general public the measures employers will take to prevent unions.

According to several workers and union representatives who described the tactics, Amazon launched an aggressive public relations campaign at BHM1, including text messages to employees, leaflets, a website urging workers to “do it for free” and flyers. posted in bathrooms urging workers to vote “NO”.

Amazon sent text messages and emails asking workers at its Bessemer, Alabama headquarters to “vote NO.”

Amazon’s greatest opportunity to influence workers came in the form of so-called captive hearings, which workers were required to attend during their shift. Amazon held weekly meetings from the end of January until the ballots were sent in early February. The workers spent about 30 minutes in PowerPoint presentations, discouraging unionization and being given the opportunity to ask questions to Amazon representatives.

Captive audience meetings are a common tactic used by employers during union campaigns. Proponents of proposed labor law reforms, such as the Law on the Protection of the Right to Organize (PRO) awaiting adoption in the Senate, argued that captive hearings serve as a forum for employers to send anti-union messages “without giving the union a chance to “The PRO Act would prohibit employers from making these meetings mandatory.

Amazon said it hosted small group meetings as a way for employees to get all the facts about joining a union and the election process itself.

The company also defended its response to the union campaign more broadly, arguing in a statement that workers “heard many more anti-Amazon messages from the union, political decision-makers and the masses.” than they heard from us ”.

Why some voted “no”

Amazon’s messaging during the meetings was more convincing for some BHM1 workers than for others.

An employee of Bessemer, who started working at Amazon last year, said he felt Amazon used some scary tactics when talking to union workers, but told CNBC he did not understand how the union would help union workers. at BHM1. The person, who requested anonymity to prevent retaliation, said RWDSU did not explain what they would do to the workers and did not respond to his request for information on how they helped employees in other jobs.

Beyond his doubts about RWDSU, this employee said he also had a positive experience primarily working for Amazon. While some workers complained about the stressful and demanding nature of the job, he said that a previous job in construction had prepared him for the physical work of the warehouse works, so he is easy. Amazon’s pay and benefits are also a step back from its previous job.

In the end, this worker voted against unionization.

In private Facebook groups, where Amazon workers engage with each other, other BHM1 employees shared their thoughts on the union campaign. One worker feared that if the union voted, employees would lose access to certain benefits offered by Amazon, such as its training program, where Amazon pays a percentage of tuition costs to prepare warehouse workers for jobs in other areas with high demand.

Another worker felt that a union was not necessary, saying that if you work hard, you can succeed at Amazon: “I voted no. Amazon is just a game, with rules. Learn the rules, play the game, go up, win . “

Mandatory meetings

Some BHM1 workers thought Amazon’s anti-union messages were too aggressive.

A BHM1 employee working as a stower, which involves transferring items to free storage bins throughout the unit, said Amazon designed the texts, leaflets and mandatory meetings to send a message that the union would not help anyone. This worker requested anonymity out of concern for job loss.

The worker, who voted for the union, said he was worried about showing support for unionization in front of Amazon and his colleagues and was nervous about asking questions, instead of fooling around so as not to be fired.

Aerial view of the Amazon facility where workers will vote on unionization, in Bessemer, Alabama, March 5, 2021.

Dustin Chambers Reuters

In a mandatory meeting held before the distribution of ballots in February, this worker said, Amazon sought to question how workers’ contributions would be spent, telling workers that RWDSU spent more than one one hundred thousand dollars a year on employee vehicles. The worker was skeptical about Amazon’s presentation, believing that Amazon probably spent a lot more on cars each year than the union did.

The President of the Union, Stuart Appelbaum, said in an interview that RWDSU buys cars for some representatives whose mission is to travel from work to work to organize campaigns.

Amazon said it wants to explain to workers, especially those who have no prior knowledge of unions, that a union is a business that collects dues and explains how those dues can be used.

In another mandatory meeting, the two Bessemer workers told CNBC, Amazon distributed examples of previous contracts that RWDSU had won, trying to highlight the union’s shortcomings. Amazon also stated that RWDSU was primarily a poultry union, which had limited experience representing warehouse workers.

Appelbaum said poultry workers make up a significant share of RWDSU membership in Alabama and many of the organizers who led the campaign and approached Amazon workers outside of BHM1 as they ended their shift from nearby poultry factories. Union it also represents workers in other industries, including retail, food production, non-profit and cannabis, said RWDSU spokesman Chelsea Connor.

In response to questions about RWDSU’s characterization as a poultry union, Amazon said it was trying to highlight to workers how well (or poorly) the union could understand its employer.

During the meetings, Amazon also sought to highlight the negative results that could emerge from the vote for the union. Amazon told workers that the union could force workers to go on strike and that employees could lose their benefits in the future, workers told CNBC.

RWDSU’s Mid-South Bureau, which led the organization at Amazon, countered Amazon’s claim that the union would force BHM1 workers to go on strike, calling it a “fear tactic,” according to communications distributed to workers.

“Amazon has hinted that the union will ‘strike you,'” Randy Hadley, chairman of the Mid-South Council, said in a letter to workers in February, addressing other claims made by Amazon. “Here are the facts, membership and membership NO MORE controls whether to hit or not with a super majority. This means that almost 4,000 Amazon workers would have to vote to strike. A strike can be useful when needed, but it is also very, very rare. This is yet another Amazon fear tactic. “

Amazon said it was trying to show workers that if a union is voted on, the union could call a strike because it is the union’s main lever over an employer.

In response to questions they asked if it told workers they could lose benefits if a union is voted on, Amazon said it sought to inform employees, as part of general union education, that there are many results that can results from collective bargaining.

Not the last effort

Amazon employees, labor leaders and workers’ supporters hope the loss of Alabama will not be the last attempt to organize the retail giant’s extensive workforce.

There may be future campaigns at BHM1. The worker who voted for the union said some pro-union employees had discussed the possibility of approaching Teamsters and continuing a future union campaign at their depot.

Elsewhere, Amazon workers and unions are considering different organizational strategies. Teamsters communicates with Amazon drivers and warehouse workers at an Iowa facility and considers ways to gather workers beyond the election process. Amazon workers in Chicago formed a group to organize employees at facilities in the area, called United Amazons Chicagoland.

A worker at an Amazon unit in New Jersey, who also requested anonymity, said he had previously addressed a union about organizing their unit. After seeing the result in Bessemer, the worker said they return to the drawing board and look for more informal tactics to get leverage.

Susan Schurman, a professor at Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, pointed to Alphabet Workers Union, a recent union of more than 800 Google employees, as a potential role model for Amazon workers.

Unlike a traditional union, minority unions do not represent the majority of workers. They are also not recognized by the NLRB and do not act as bargaining agents with employers.

However, Schurman said minority unions can serve as a “path to majority unions” and can be a powerful tool for building worker support even before launching a formal campaign with the NLRB.

“Why not stay and build an organization and stick to it?” Said Schurman. “Let workers recruit new members and demonstrate the value of collective bargaining power.”

Appelbaum, president of RWDSU, said a minority union strategy was “worth thinking about”.

“We have not yet made a decision on this, but I think we will analyze it,” Appelbaum said. “We know we’re not leaving.”