Follow the twisted limbs of the family tree to its primordial origins billions of years ago and you will discover that we all originated from dust rich in organic chemistry.

Exactly where this organic dust came from has been a topic of debate for more than half a century. Now, researchers have found the first evidence of organic materials essential to life on Earth on the surface of a S-type asteroid.

An international team of researchers recently conducted an in-depth analysis of one of the particles brought from the asteroid Itokawa by the original Hayabusa mission of the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) in 2010.

Most of Earth’s meteorites come from S-type asteroids, such as Itokawa, so knowing that they could contain essential ingredients for life on our planet is a significant step forward in understanding how life-forming conditions might occur. To date, most research on organic materials has focused on high-carbon asteroids (class c).

Looking at the sample, the team found that the organic material that came from the asteroid itself evolved over time under extreme conditions – incorporating water and organic matter from other sources.

This is similar to the process that took place on Earth and helps us better understand how the early forms of terrestrial biochemistry could simply be an extension of the chemistry that takes place inside many asteroids.

“These discoveries are truly exciting because they reveal complex details of an asteroid’s history and how its evolutionary path is so similar to that of prebiotic Earth,” says Earth scientist Queenie Chan of Royal Holloway University in London.

Evolutionary models can take us back about 3.5 billion years to a time when life was little more than competing nucleic acid sequences.

Take a step back and we are forced to consider how elements such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and carbon could come together to form amazingly complex molecules capable of self-arranging into things that behave like RNA, proteins. And fatty acids.

In the 1950s, as researchers first thought about the poignant question of how simpler ingredients could spontaneously cook an organic soup, experiments showed that conditions on the Earth’s surface could do enough work.

Nearly seven decades later, our attention has shifted to the slow, steady chemical processes inside the rocks that have aggregated into worlds like ours.

Evidence is not hard to find. It is now clear that a constant rain of rock and ice billions of years ago could have delivered cyanide molecules, ribose sugar and even amino acids – along with a generous donation of water – to the Earth’s surface.

But the extent to which meteorite chemistry could have been contaminated by things on Earth leaves room for doubt.

Since Hayabusa’s return a decade ago, more than 900 particles of clean asteroid dirt taken from his payload have been separated and stored in a clean JAXA room.

Less than 10 have been studied for signs of organic chemistry, but all have been found to contain molecules composed mainly of carbon.

Itokawa is what is called a stony (or silicon) class of asteroid or class s. Early studies of its material are also thought to be a common chondrite – a relatively unchanged type of space rock that represents a state. more primitive of the inner solar system.

Given that these types of asteroids make up a large part of the minerals that break down on our planet and are not generally believed to contain too much in organic chemistry, those early discoveries were, to say the least, fascinating.

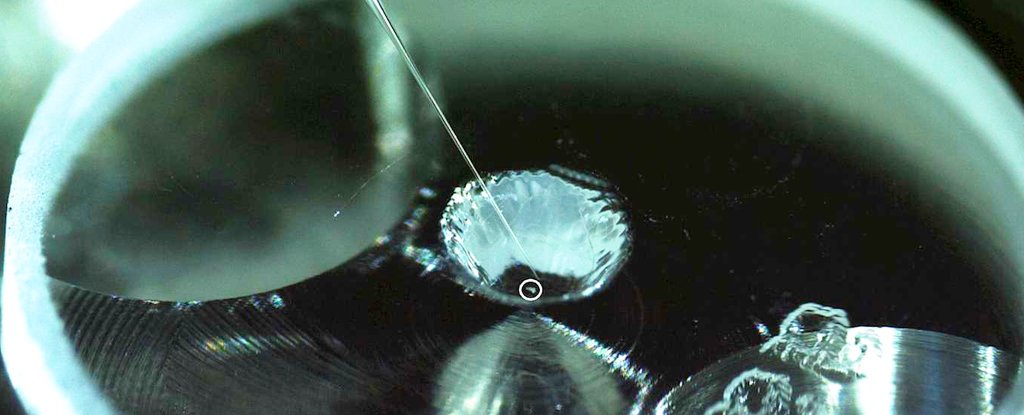

Chan and her colleagues took only one of these dust grains, a 30-micrometer-wide particle in a shape somewhat similar to that of South America, and conducted a detailed analysis of its composition, including a study of its water content.

They found a rich variety of carbon compounds, including signs of disordered polyaromatic molecules of clear extraterrestrial origin and graphite structures.

After being studied in detail by an international team of researchers, our analysis of a single grain, nicknamed “Amazon”, preserved both primitive (unheated) and processed (heated) matter within ten microns ( a thousand centimeters) away, “says Chan.

“The organic matter that has been heated indicates that the asteroid has been heated to over 600 ° C in the past. The presence of unheated organic matter very close to it means that the fall of the primitive organs reached the surface of Itokawa after the asteroid cooled. “

Itokawa has had an exciting history for a stone that has nothing better to do than float in a vacuum around the Sun for several billion years, being modified with a good baking, dehydrated, then rehydrated with a new layer of fresh material.

While its story is not as interesting as the history of its own planet, the asteroid’s activity describes the cooking of organic matter in space as a complex process and is not limited to high-carbon asteroids.

Late last year, Hayabusa2 returned with a sample of a c-class asteroid close to Earth called Ryugu. Comparing the contents of its payload with those of its predecessor will undoubtedly contribute to a better understanding of how organic chemistry evolves in space.

The question of the origins of life and its apparent uniqueness on Earth is one to which we will seek answers for a long time. But each new discovery tells a story that stretches beyond the safe, warm puddles of our newborn planet.

This research was published in Scientific reports.