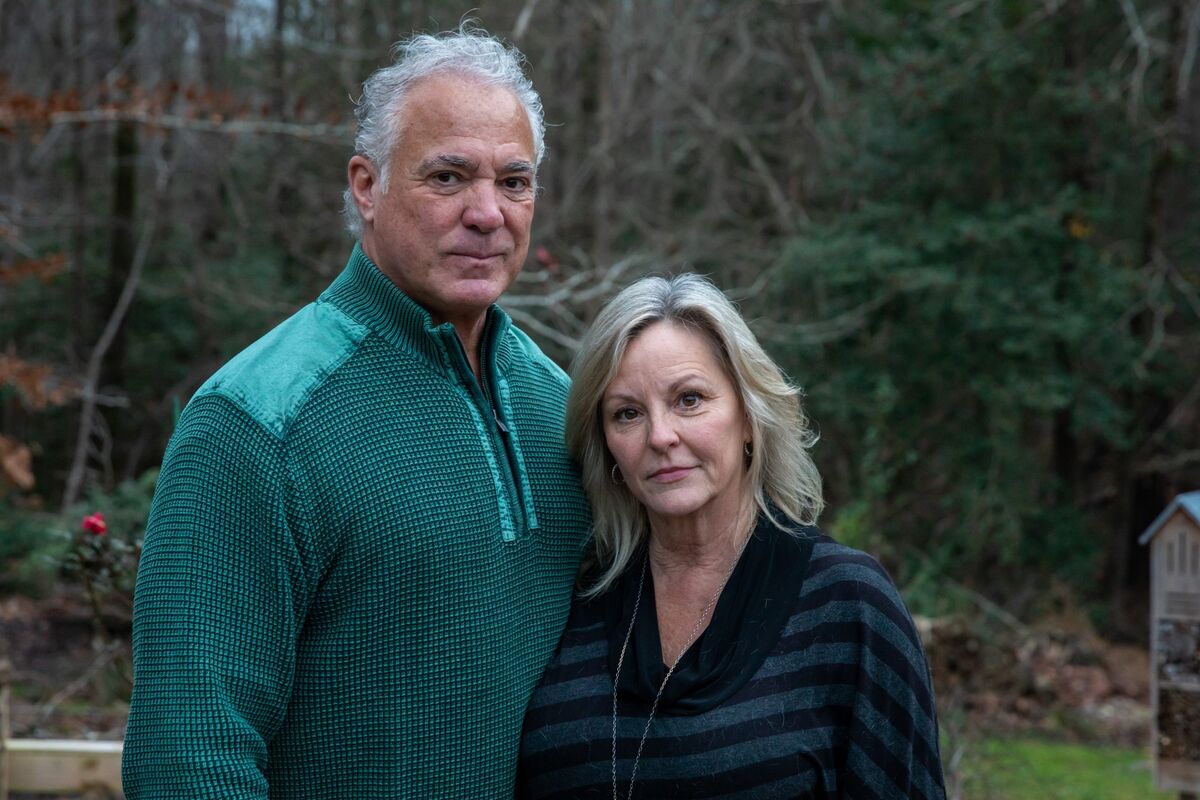

Cindy and Mark Bezzek at home in Sanford on December 17th.

Photographer: Rachel Jessen / Bloomberg

Photographer: Rachel Jessen / Bloomberg

Cindy Bezzek and her husband built their home in Sanford, North Carolina, to be an oasis with bonsai, turtles and a koi pond with waterfall flanks. The place called Tranquility Ranch was Bezzek’s refuge after years of tumult. Her mantra when the year 2020 began: “Look for beauty”.

Then came spring, when Mark Bezzek, a doctor, began treating patients so ill that they died no matter what he did. When Mark’s mother contracted Covid-19 and died. When an assisted living unit interrupted Cindy’s visits with her own mother, Louise Hope. When the 92-year-old stopped eating and wasted himself.

When, as Cindy had feared, her 33-year-old daughter, Marley, overdosed for the last time.

The pandemic that began 8,000 miles away in a corner of a Chinese market has overtaken the Tranquility Ranch defense. With her four-year-old husband plunged into medical crisis and friends and family unable to visit freely, Bezzek, a 62-year-old retired mother, was left alone.

Photos of Cindy Bezzek’s late mother, Louise Hope, and her daughter, Marley Atamanchuk.

Photographer: Rachel Jessen / Bloomberg

“It simply came to our notice then. You just feel like you need heaven because your pain is so great. If you’re inside, it feels like you’re going to suffocate, “said Bezzek, who has vocals from a lifetime spent in North Carolina. “My daughter is gone. My mother is gone. And I’m still here. “

Globally, 2020 was a year of losses: education, jobs, health and lives. The United States, whose federal government has refused aggressive measures to combat the pandemic, has recorded more than 19 million cases of Covid-19 and 333,000 deaths, mostly among the elderly and people of color. 130,500 Americans are expected to die this year from other causes, above historical averages. At least one factor: With the elimination of relatives and support systems, drug overdoses and mental health crises have increased.

However, for all that families like Bezzeks have endured, 2021 will start the same as the year before. By April, another 209,000 in the United States could die from Covid-19, according to one model. While calculating the impact of lost lives, productivity and health, economists and academics predict long-term effects on the mental health of those who have experienced the pandemic. Families in the US are already facing this tax.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon in December, Bezzek has a video visit with two of his three sisters. The eldest, Bonnie Allen, continues to cough – hacking, indeed. She doesn’t smell or taste and drives her crazy, she tells her sisters. Symptoms have ruined her plan to visit her niece in Pittsburgh, who is having a sixth unicorn-themed birthday party.

Cindy Bezzek

Photographer: Rachel Jessen / Bloomberg

“Maybe it will change,” Bezzek tells her sisters. “Maybe the vaccine will be miraculous and things will open up and we will be able to return to a better life.”

Maybe, says Allen. But he read that even after a vaccine, we will need masks and social distance.

“I’m just trying to find hope for 2021,” says Bezzek.

“We only have three weeks left,” says Allen.

“Fortunately,” Kari Crow pipes in Katy, Texas, still the family’s 50-year-old baby.

The day after they spoke, Allen’s test result was positive.

Covid-19 has been running the family for months. In April, the sisters gathered when their mother contracted the disease.

Believing it was the end, the assisted living unit in Pittsboro, North Carolina, let them visit, says Bezzek. When Louise Hope gathered, the house stopped visiting again. Then he stopped eating. Her daughters believe she felt abandoned and isolated. Bezzek was able to visit her in his mother’s last days, but he arrived too late in the afternoon of July 22 to be with Louise when she died.

“Covid didn’t kill her, but his broken heart did, I think,” Allen says.

A memorial stone for Cindy Bezzek’s late daughter, Marley, in the family yard.

Photographer: Rachel Jessen / Bloomberg

Louise Hope had seven children, raising them in Alabama and then North Carolina, where she and her daughters became members of the island Church of God around the world, which some called a cult. There, an 18-year-old Bezzek met and married her first husband and the father of her three children, including Marley.

After the divorce, she left the church, remarried a developer, and helped manage the properties she rented to students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. That marriage collapsed in 2015, eroded by years of trying to help Marley. She met Mark Bezzek online that year, texting the 62-year-old doctor for emergency medicine because she liked his smile. They got married a year later and moved to Tranquility Ranch in 2018.

They lost 82-year-old Mark’s mother in June. He was already suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, contracted Covid-19 in a nursing home in New Jersey, and died a week later. Until they got the call, they didn’t even know about the diagnosis, he says.

Stoic, with white hair, with a wide and injured face, Mark Bezzek has been surrounded by illness for months, often working without sufficient protective equipment. Even with the trauma of his family, the job prevented Mark from taking days off. His hospital sees more Covid-19 patients than ever before, and with a limited number of nurses, every bed with staff is full.

“It is difficult to cope with the losses at home and at work. You are surrounded by death all the time, “he says. “One of the things I have about Cindy is that I worked with death. I have been surrounded by this my whole career. Eventually you become, I wouldn’t say with a heart of stone, but you become a little less passionate about death. “

Meanwhile, Cindy has been haunted for years by the prospect of a singular death. Marley Atamanchuk had contracted opioids in her late teens. He got married, had children and became an esthetician. Nothing stopped the cycle of treatment, recovery and recurrence.

Cindy and Mark Bezzek

Photographer: Rachel Jessen / Bloomberg

The pandemic did not stop America’s addiction crisis – instead, driving forces such as economic despair and social isolation intensified. Overdose deaths, already on the rise, appear to be accelerating, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently warned. More than 81,000 such deaths occurred in the year to May, the most ever recorded in a 12-month period, according to the agency.

Marley was fired this year, and Bezzek saw signs of a drop. Insurance through the Affordable Care Act paid for a program, but Marley returned to a world without personal assistance meetings and struggled to find the same connection through Zoom offers.

Just two weeks after the death of her grandmother, who gave Marley her middle name, Louise, she overdosed on heroin, dying days later.

The Hope sisters visited North Carolina again in August, while Marley lay in a hospital bed. But when it came time to lift her ashes from the funeral home, Bezzek was alone. She drove alone and tied the urn to the passenger seat. Neither Marley nor Louise Hope had a funeral.

Lately, Bezzek spends his days meditating and reading books about death and the afterlife. For the rest of the year, she gave herself a free permit: to eat sugar at every meal or not to wash her face. But in January, he has to get up and start moving again; can start something voluntarily, if Covid allows.

She did not choose a mantra for 2021. She thinks it will be about coming home to herself. Finding ways to move forward.