They were not scheduled to return to Earth until April 28 at the earliest, so why NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover and Shannon Walker, along with Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut Soichi, dressed and they boarded the Crew Dragon Resilience on April 5? Because a previously untested maneuver meant that after they closed the hatch between their spaceship and the International Space Station, there was a chance that they would not return.

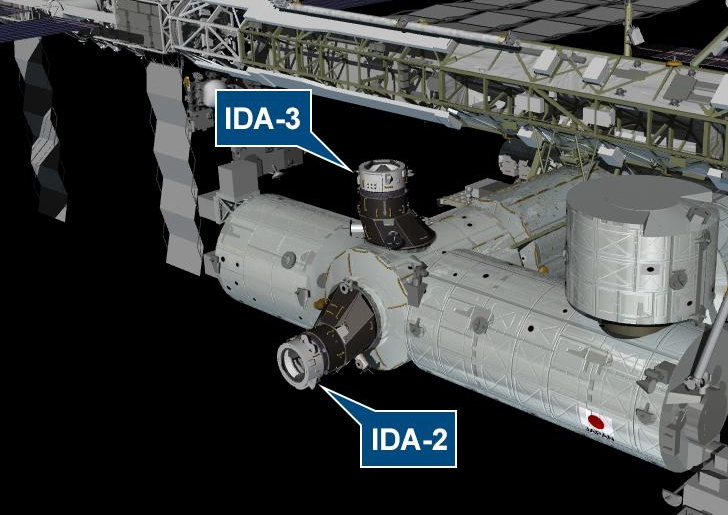

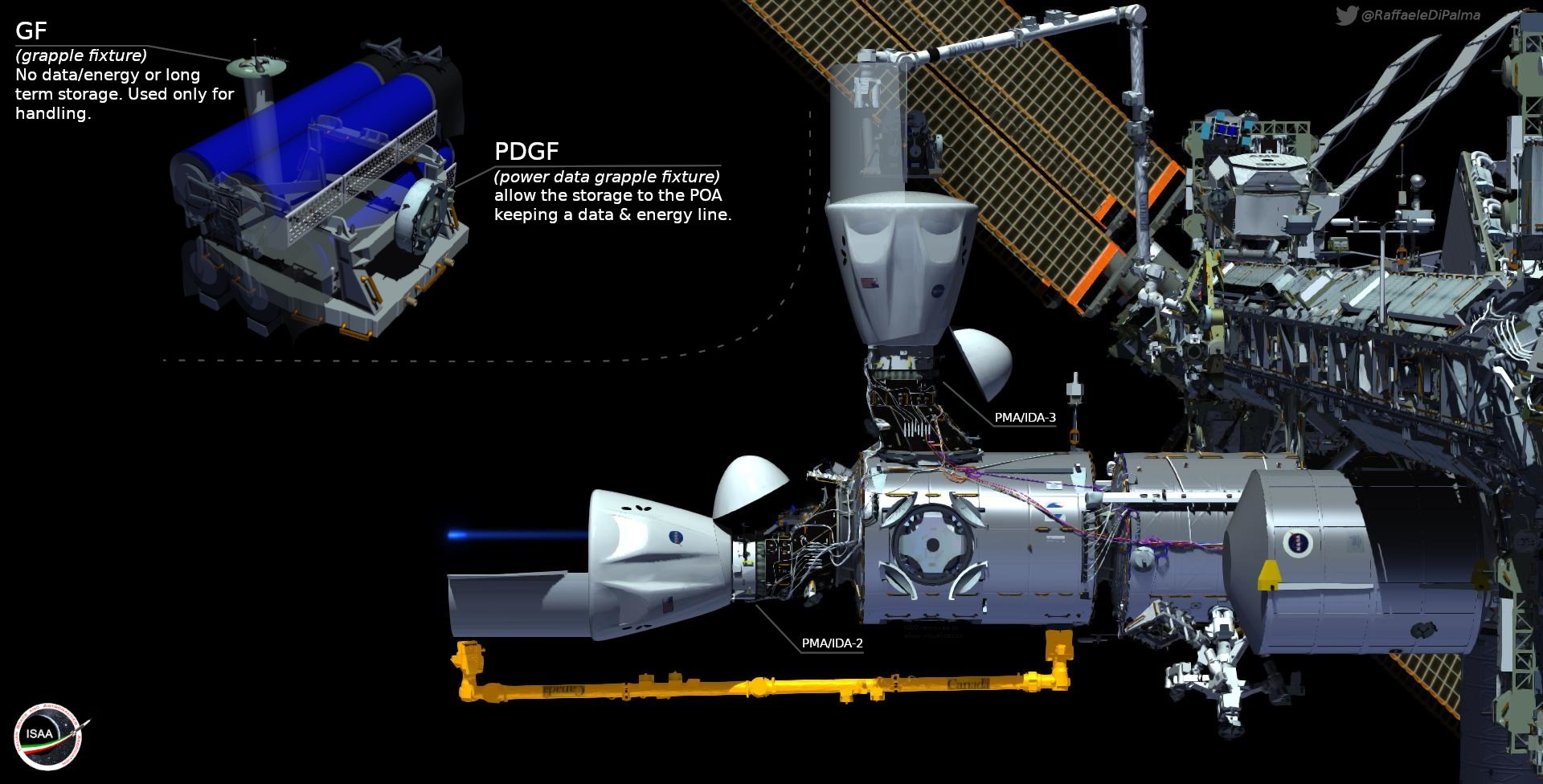

On paper, moving a capsule between dock ports seems simple enough. All Resilience we had to disconnect from the international docking adapter 2 (IDA-2) located on the front of the Harmony , attached to the pressurized pairing adapter 2 (PMA-2), which was once the orbital parking space for the space shuttle and moves to PMA-3 / IDA-3 at the top of the Harmony. It was a short trip through open space and, when the crew got out of the boat and re-entered the station at the end of it, it would have been only a few meters from where they started about 45 minutes before.

What if the vehicle had a problem that prevented it from returning to the ISS? An American spacecraft has never attempted a move like this, much less a commercial one like the Crew Dragon. So, while the chances of such a misfortune were small, the crew still treated this short flight as if it could be their last day in space. Should the need arise, all necessary checks and preparations have been made so that the vehicle can bring its occupants to Earth safely.

Fortunately, it was not necessary. Autonomous relocation of Crew Dragon Resilience they disappeared without a hitch and SpaceX had to add another “bonus” to their ever-growing list of achievements in space. But this first move of an American spacecraft to the ISS will certainly not be the last, as the arrival and arrival of the commercial spacecraft will only become more complex in the future.

Unprecedented activity

During the space shuttle, NASA did not have to worry about relocating their spacecraft, as there was never more than one of the orbiters flown into space at the same time. But since the shuttle was capable of carrying seven crew members and an incredible amount of cargo simultaneously, this was not a problem. All of NASA’s operational needs on the ISS were more than met by a single vehicle.

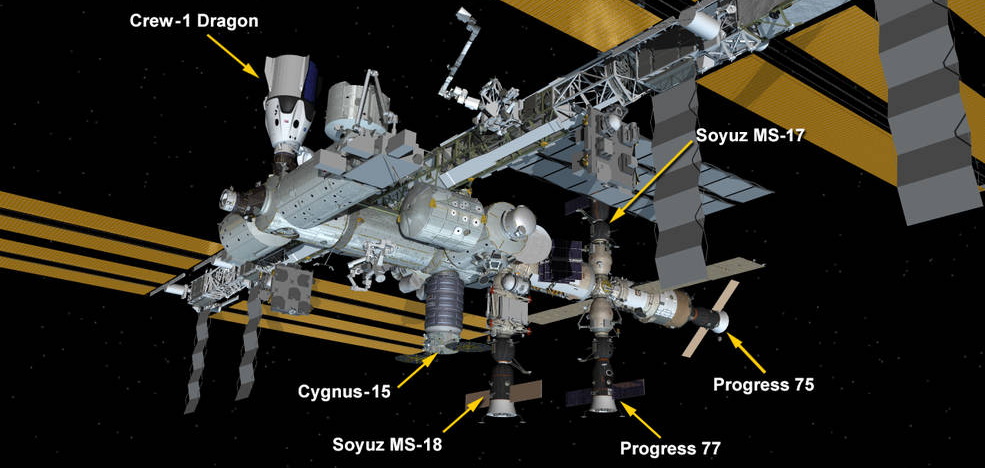

Of course, all that changed when Shuttle was withdrawn in 2011. NASA began trading with its international partners and eventually even with commercial companies to bring crew and cargo to the station on a wide range of smaller and more operationally agile spacecraft. Today, these vehicles, in addition to Russia’s Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, occupy most of the available docking and docking ports on the ISS at one time. In the coming years, more commercial spacecraft are expected to be brought online, which means that traffic will only get worse at the orbiting outpost.

With the US segment of the ISS now busier than ever, NASA faces a logistical challenge that its Russian counterparts are already well accustomed to. It may have been the first time an American spacecraft had had to be moved to another dock during a mission, but so far, 19 Soyuz capsules have had to make similar trips; the most recent of these just took place a few weeks earlier, on March 19th.

A complicated dance

Given that Resilience it ended up moving to a docking port just a few meters away from where it was originally, it is easy to believe that everything was a kind of experimental proof of the concept. Maybe as a test for future, more complex maneuvers. But in fact, the two international docking adapters are currently the only places on the ISS where commercial vehicles such as the Crew Dragon, the Boeing Starliner capsule and, finally, the Dream Chaser space plan in the Sierra Nevada can be attached. In short, while the destination will alternate, port relocations for American spacecraft will always be a short leap.

But why? What difference could a journey made over such a short distance make? The answer lies in the unique design of the Dragon’s Cargo variant, which can carry large bulky objects in the empty “trunk” behind the pressure capsule. In general, the cargo brought behind the cargo dragon is intended to be mounted outside the station and is recovered from the spacecraft using the robotic arm of the orbiting laboratory. As it happens, both IDA-2 and IDA-3 were delivered to the station in 2016 and 2019.

The trick is that the Station arm cannot reach the Dragon’s trunk if docked Harmony port forward. That’s not a problem right now because Resilience does not carry any external cargo. But it will be in June, when a Dragon Cargo delivers a new set of solar matrices that can be implemented for the Station as part of the CRS-22 mission. To complicate matters further, four more astronauts are due to dock with the Station at the end of April aboard the Dragon crew. Effort.

That means Resilience necessary to switch to PMA-3 / IDA-3 so Effort may dock at PMA-2 / IDA-2 at the end of the month. Then once Resilience leaves, the top docking port will be free to accept CRS-22 in June so that the solar molds can be removed from the trunk with the robotic arm. After leaving CRS-22, Effort it will have to make its own jump up and up to PMA-3 / IDA-3, as a Boeing Starliner has to dock at PMA-2 / IDA-2 as part of its first test flight to the station in July.

Does it sound complicated? That’s because it is. But, unfortunately, for NASA, unless commercial expansion plans for the International Space Station pass, this is the orbital game of “musical chairs” they will be forced to deal with. With only two viable docking ports available for current and future spacecraft, the United States should quickly catch up with its Russian counterparts when it comes to the plastic art of spacecraft juggling. Except now, these moves will be autonomous.