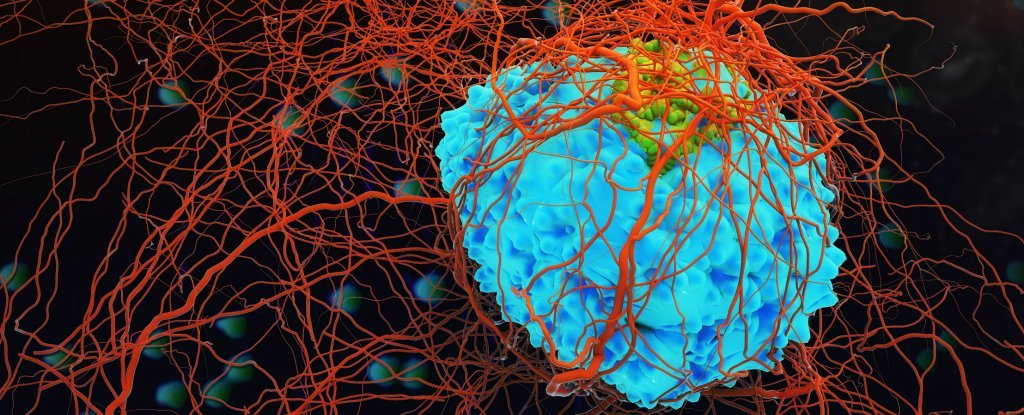

Cancer cells are able to hibernate like “bears in winter” when a threat such as chemotherapy treatment strikes them, according to new research – apparently adopting the tactics used by some animals (though long lost to humans) to survive in which resources are scarce.

Accurate knowledge of how cancer is evaded and subjected to drug treatment is an important part of efforts to defeat them permanently, which is why understanding this hibernation behavior could play a crucial role in future research. Cancers can often return after they remain dormant or apparently disappear after a few years after treatment.

Preclinical research on human colorectal cancer cells has shown that they have managed to slow down in a state of low-maintenance “drug tolerance persistence” (DTP), which would help explain therapy failures and tumor recurrence.

“The tumor acts as a whole organism, able to enter a state of slow division, conserving energy to help it survive,” says researcher and surgeon Catherine O’Brien of the Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Canada.

“There are examples of animals that enter a reversible and slowly dividing state to withstand harsh environments. It appears that cancer cells have ingeniously co-opted this same condition for the benefit of their survival.”

By collecting human colorectal cancer cells in a Petri dish and exposing the cells to chemotherapy, the researchers observed that the colorectal cancer cells enter the same state of hibernation, in a coordinated manner, when chemotherapy drugs were present. The cells have stopped expanding, which means they need very little nutrients to survive.

These observations “also fit a mathematical model in which all cancer cells, and not a small subpopulation, possess an equipotent capacity to become DTP,” suggesting that these survival strategies could be seen in all cancer cells.

The researchers also used colorectal cancer cell xenografts on different sets of mice. Once the mice developed tumors of a certain size, the researchers treated the mice with standard chemotherapy regimens. The scientists observed a negligible increase in the tumor in mice receiving treatment for an eight-week period. When treatment stopped, the growth of the tumor began again.

Cancer cells taken from tumors after a period of growth were then grafted into different mice and treated again. The regenerated cells remained sensitive to treatment, and their growth stopped and began in the same way, findings consistent with the entry of cancer cells in a state of DTP.

This DTP condition is very similar to a hibernation-like condition, called embryonic diapause, in which mouse embryos fall again as a kind of emergency survival mode. Embryonic diapause allows many animals, including mice, to effectively put embryonic development into a break until environmental conditions are more favorable.

Here, the cancer cells were found doing a similar trick. Another link between DTP status and embryonic diapause is their dependence on a biological mechanism called autophagy, in which cells eat, in essence, to find the food they need. Autophagy occurs naturally in the body as a way to eliminate waste, but in this case cancers use it to stay alive.

“I never knew that cancer cells look like bears hibernating,” says oncologist Aaron Schimmer of the Princess Margaret Cancer Center. “This study also tells us how to target these dormant bears so they don’t hibernate and wake up to come back later, unexpectedly.”

“I think this will prove to be an important cause of drug resistance and will explain something we didn’t have a good understanding of before.”

By directing and inhibiting the autophagy process, the researchers were able to break the hibernation state (or DTP) and permanently destroy the cancer cells with chemotherapy. This could be an approach to addressing cancer tumors that are resistant to conventional treatments in the future.

Scientists already know about a few other ways in which cancer can hide in the body, so this new study adds to a growing collection of evidence on how to take over cancer cells that are most resistant to drugs and current approaches.

“This gives us a unique therapeutic opportunity,” says O’Brien. “We need to target cancer cells while they are in this slow, vulnerable cycle before they acquire the genetic mutations that lead to drug resistance.

“It’s a new way of thinking about resistance to chemotherapy and how to overcome it.”

The research was published in Cell.