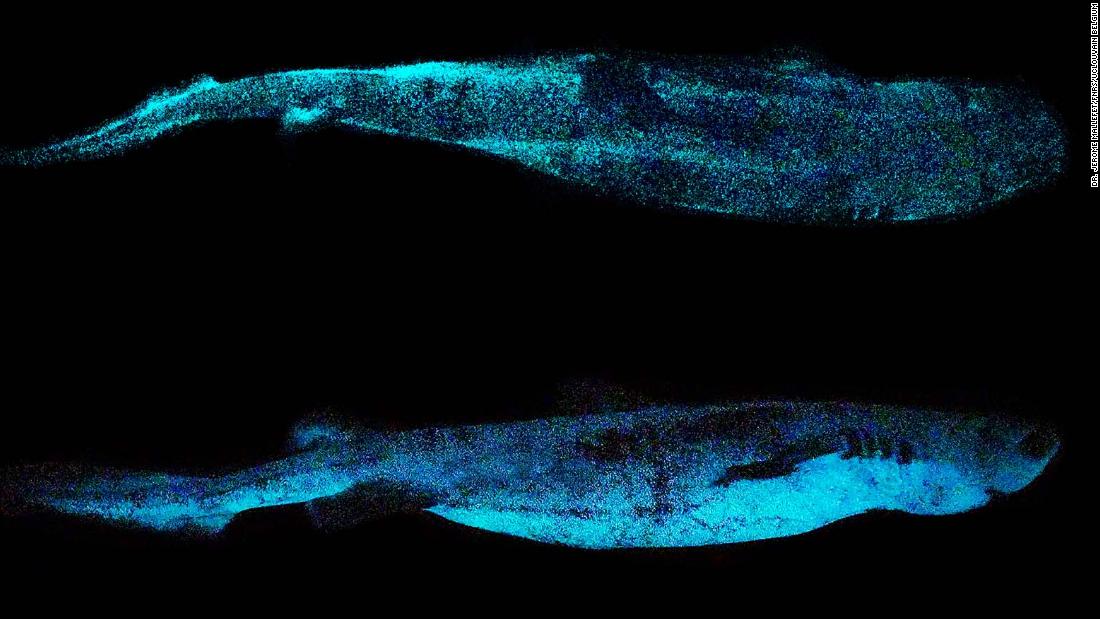

Bioluminescence refers to the production of visible light by living organisms through a biochemical reaction. About 57 of the 540 known shark species are believed to be capable of producing light, study co-author Jérôme Mallefet, head of the marine biology lab at UCLouvain, told CNN on Wednesday.

While specimens had previously shown that kite sharks should be able to produce light, they are “really hard to spot” because they live between 200 and 900 meters (656-2,953 feet) below the ocean’s surface, Mallefet said.

Bioluminescence has also been documented in two other deep-water shark species, Etmopterus lucifer (black-bellied shark) and Etmopterus granulosus (southern flashlight shark), as part of the research.

Mallefet noticed that the sharks were caught accidentally during the NIWA trawl surveys, which are used to measure fish stocks, and contacted the organization.

He was invited to join a survey voyage in January 2020 and spent 30 days aboard the ship, catching several sharks.

“I was just like a child at the bottom of a Christmas tree,” Mallefet said, describing how he managed to take a picture of a kite shark in a bucket in a dark room of the ship.

The sea depth of less than 200 meters (656 feet) is described as the twilight zone. Many people mistakenly believe that there is no visible light there, but there is a light that sharks find useful, Mallefet said.

“I use light to make them disappear,” he said, explaining how bioluminescence can make sharks invisible against the faint glow of the ocean’s surface.

This protects sharks from predators swimming under them and also makes it easier for them to hunt prey, Mallefet said.

“We know this is the case with Dalatias licha,” he said, as the remains of smaller sharks were found inside the bellies of some specimens, despite the fact that the species is the slowest swimming shark in the world.

However, bright sharks have not given up all their secrets, including why their dorsal fin shines.

Further research is needed to find out if this could be used for signaling, Mallefet said, adding: “There are still question marks.”

Mallefet told CNN that he would like to study the dorsal fin in more detail in future trips to the area, as well as analyze what sharks eat and whether they are eaten.

The goal is to learn more about the deep sea, which remains mysterious, despite being the most common environment on Earth, to make people think more about its conservation, he said.

“I’m afraid I’ve made a lot of mistakes throwing things into the sea,” Mallefet said. “I am afraid of what will happen to future generations.”